The best possible shot to save the one planet we’ve got

Five years after its signing, we reflect on the Paris Climate Accord's journey and the critical work that remains.

Five years ago this week, the Paris Climate Agreement took effect, as nearly 200 nations committed to reduce their carbon emissions for the first time.

To mark this milestone we asked ten people—Obama Administration alumni, Obama Foundation leaders on the front lines of the climate fight, and President Obama himself—to reflect on the path to Paris and the work that remains to address the climate crisis.

The One Planet We've Got

The Paris Agreement remains one of President Obama’s proudest accomplishments. It committed nearly all nations to binding emissions reductions and capstoned a longer effort that stretched across President Obama’s two terms to reduce our reliance on fossil fuels. By the time he left office, those efforts helped create a vibrant clean energy industry in the United States, while reducing America’s carbon pollution to its lowest levels in two decades. His personal diplomacy also helped bring nations like China and India into the fold, forging a truly global framework to fight climate change.

But even as the agreement in Paris was reached, President Obama underscored that the agreement alone was not enough to address the crisis; instead, Paris provided a framework for increased ambition in the fight against climate change, including through summits like the one taking place in Glasgow next week. Many of the young leaders the Obama Foundation supports are on the front lines of the climate fight and the Foundation has created communities of practice to share ideas and resources with program alumni as they engage in this work.

Nearly every day, we see new evidence of how rising global temperatures affect our lives in the form of rising sea levels, longer droughts, more intense wildfires, and record-breaking storms, all of which contribute to the collapse of communities around the world. Progress requires all of us—activists, business leaders, governments—to ask what more we can do to live up to and build upon commitments like those made in Paris.

As President Obama notes, “we’ve got no time to lose.”

An Existential Crisis

President Barack Obama: I came into office deeply concerned about what was a slow-rolling, but accelerating crisis, as global temperatures went up as a consequence of the increase in greenhouse gases. When I ran in 2007, 2008, I knew this was going to be a top priority of my administration. What we didn’t count on was the fact that as I entered office, we were in the worst global financial crisis (Opens in a new tab) and economic crisis since the Great Depression.

So one of the things that we had to figure out was, how are we going to deal with people losing their jobs, their homes, global trade collapsing? How are we going to make sure that the banking system doesn’t implode at the same time as we’re advancing what was going to be a heavy lift in terms of dealing with climate change?

John Podesta, former Counselor to the President: In 2008, Senator Obama asked me to run the transition. And so as we came into 2009, we were trying to make good on the pledges that he made during the course of the campaign, which were really to take climate change seriously, to make major investments in clean energy.

Carol Browner, former Director of the White House Office of Energy and Climate Change Policy: Even before we got to the White House, starting in November after the election…we were thinking about what tools he had available under existing law to address climate change.

I went to Chicago when he was president-elect and we had this very long conversation about what he might be able to do as president. He said he wanted to create an office in the White House on climate change and energy. That had never been done before.

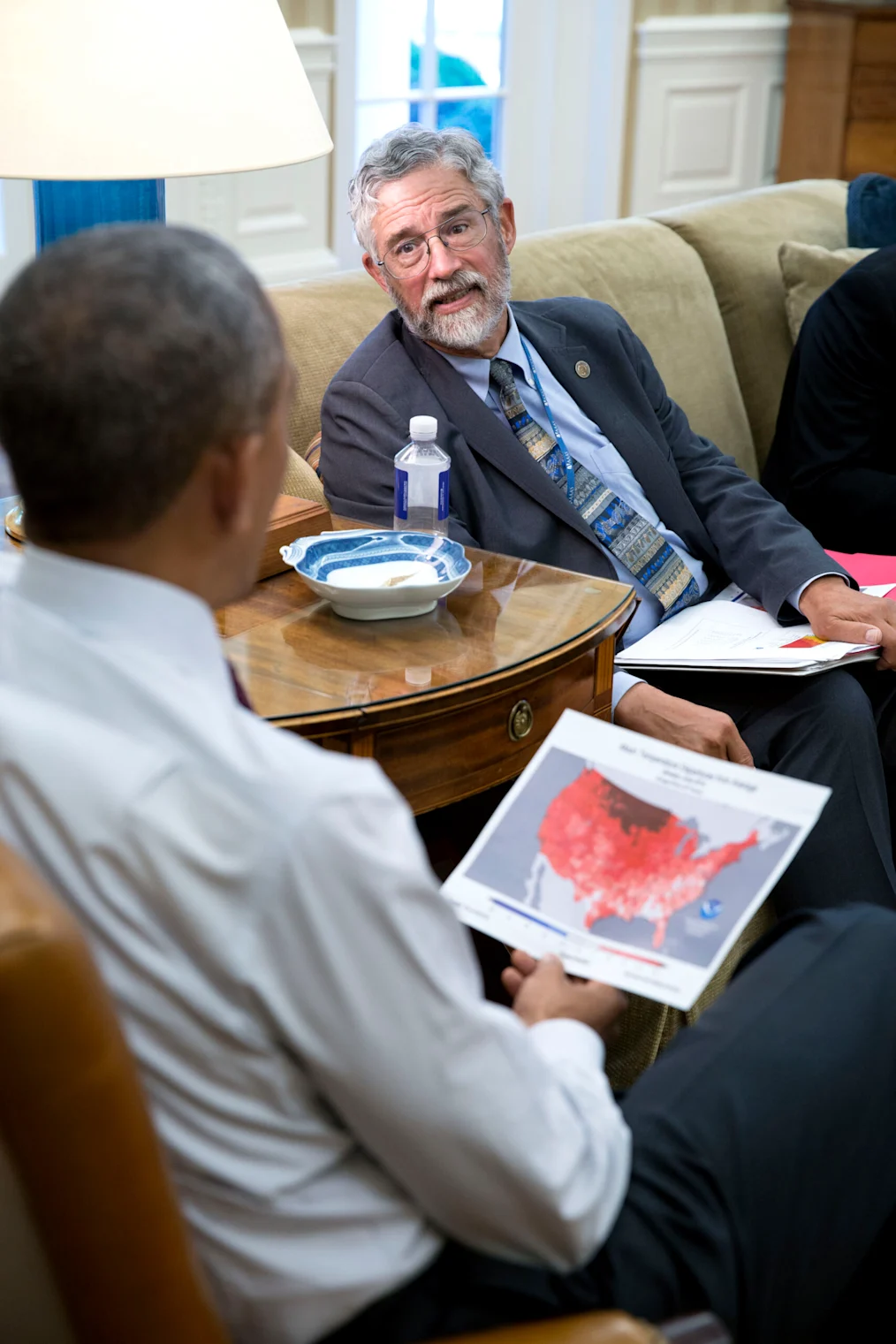

Listen to John Holdren, Former Director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, describe President Obama’s priorities on climate taking office

The One Planet We've Got: Dr. John Holdren

President Barack Obama: The issue of climate change is not one that any single nation can solve by itself. The United States had a particular responsibility to lead on this issue because we, at the time I came into office, were the largest carbon emitter. But China and other developing countries were growing very quickly, and China would soon surpass the United States as the leading carbon emitter.

Ben Rhodes, former Deputy National Security Advisor: The thing about climate change is you have some very deep structural impediments to change — you have to revise and remake the entire global economy to be able to deal with it.

So the question is where is the pressure going to come from on elected leaders to take this more seriously and to push through the objections to action that are inevitably going to come from certain entrenched interests.

Lisa Jackson, former Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency: Over eight years the President and his administration pushed this issue forward in the face of a recalcitrant opposition. First, it was, “climate change doesn’t exist”, then it was, “you’re overestimating the impacts.”

There was so much denialism and merchants of doubt out there trying to get people to believe that it was not in their best interest to address what’s literally happening outside of our windows. But the president kept at it.

President Barack Obama: The one thing I was very certain of coming into office, was that we had to feel what Dr. King called, “The fierce urgency of now.” That each year that passed, the problem got worse and it was going to be harder and harder to roll back, or at least suspend the rise in temperatures that affect everything, from increases in natural disasters, to droughts that result in migration patterns, changes that in turn can lead to conflicts.

I also understood that if we were going to be successful, we were going to have to make sure that all branches of government had an orientation towards making sure that we did something to address this problem.

Watch Obama-Biden Transition Co-Chair and Former White House Counselor to the President John Podesta describe the campaign promises President Obama looked to deliver on in office.

The One Planet We've Got: John Podesta

Early Investments and New Standards

President Barack Obama: Throughout my first term, we had to have parallel thoughts in mind: We had to, on the one hand, make sure that we were focused on the economy, and that was the number one priority of our administration and voters. But we couldn’t just set aside climate change because we had no time to waste.

Our first big initiative to save the economy was the American Recovery Act (Opens in a new tab). We were able to determine out of the $800 billion or so that we’re going to spend to stimulate the economy, can we also boost a clean energy economy that’s going to start reducing greenhouse gases?

Carol Browner: He made a choice to make the largest investment in the green economy — $90 billion — in the history of the United States (Opens in a new tab).

Watch former White House Office on Climate Change Director Carol Browner describe early efforts to invest in the American renewable energy industry.

The One Planet We've Got: Carol Browner

Carol Browner: Wall Street stopped loaning to green startup companies. They just didn’t believe in a down economy they could get the returns they needed. And so we were able to set up a Loan Guarantee Program that was run out of the Department of Energy that invested in these companies.

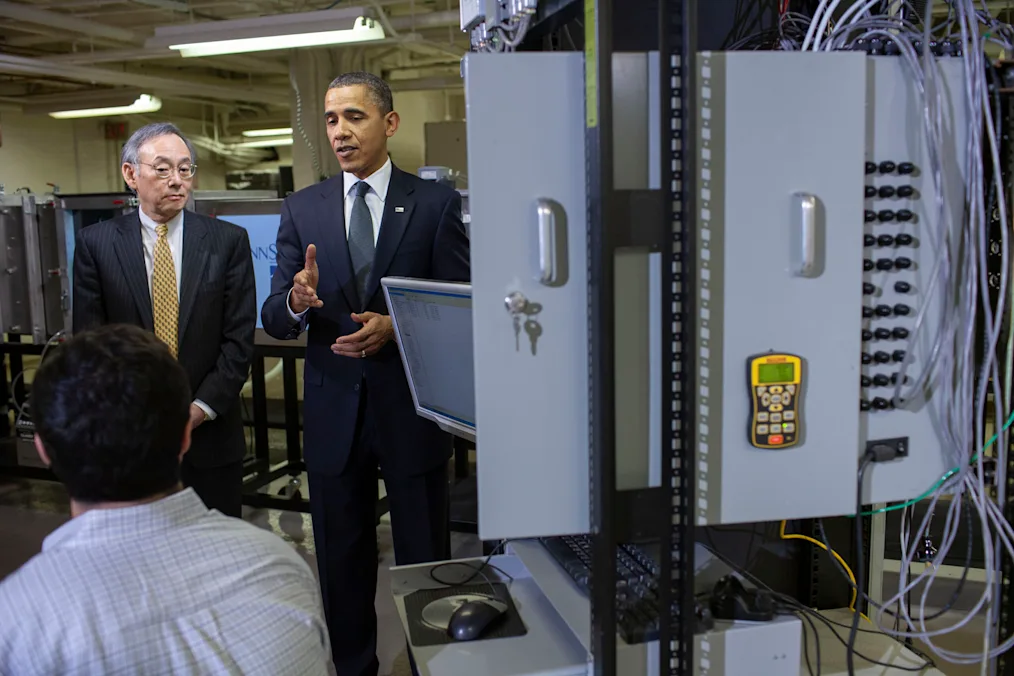

Steven Chu, former Secretary of Energy: In the Department of Energy we said, if a responsible developer could get a signed power purchase agreement contract, and if the wind and solar projects were completed on budget, on time, we felt those loans would be very safe. It was a big success in that respect.

There were notable failures. The most famous failure was Solyndra (Opens in a new tab), which was a solar company, went bankrupt. It failed like many other solar companies. The biggest solar company in China went bankrupt, as well. But when that company went bankrupt, the government came in and said, “We’ll prop you up and help you survive.”

Tesla would have gone bankrupt within weeks, had we not announced (Opens in a new tab) that we were going to give them the loan. We also made a loan to Nissan to help them to develop their Leaf in the US. On balance, the income of the loan program actually is going to break even and make a few billion dollars.

President Barack Obama: At the same time, we also had an auto crisis (Opens in a new tab), and we were negotiating with the big three automakers in the United States around figuring out how to make sure they didn’t collapse. They were hugely important to the economies of the Midwest, there were entire towns that would have collapsed had the auto industries gone belly up. And so we said, “Look, we’re committed to making sure that these car companies survive, but there are going to be some conditions…it’s time for you guys to start making cars that are more energy efficient, and work with us to raise mileage standards so that we’re putting less pollution into the air, and reducing the greenhouse gases that cause global warming.”

Lisa Jackson: The Supreme Court had said [in 2007] that it was within EPA’s purview under the Clean Air Act to determine whether greenhouse gases endanger public health and welfare. Looking back today, you would go, “this is a no brainer”, but back then, there was all this science that had been done by EPA staff to make that point so it could stand up in court.

[That eventually allowed us to announce] the “ endangerment finding (Opens in a new tab).” Without that finding, the EPA couldn’t regulate greenhouse gases.

We could be really clear that if you’re going to run a coal fired power plant, it should not be one that is surviving because it’s skirting pollution regulations. The endangerment finding and then our mercury rules for power plants helped a lot of coal fired plants that were operating on the margin at the expense of people’s health — particularly children’s health — make the decision to phase out.

Watch former EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson describe her work on environmental justice.

The One Planet We've Got: Lisa Jackson

Carol Browner: Money, tax mechanisms, regulatory authorities — we were using all of them. We were weaving them together to create more than just the sum of the parts. What came out of that is a robust wind and solar industry that is competitive today, in part, because of the investments we made. When we look across the “green” jobs in this country, this was a significant investment that we are reaping the benefits of today (Opens in a new tab).

Two Steps Forward, One Step Back in Copenhagen

In December 2009, over 100 world leaders gathered in Copenhagen for COP15 (Opens in a new tab), a United Nations conference, in hopes of creating a global agreement to address climate change.

John Podesta: During the end of the Clinton administration, there was a negotiation under the Climate Change Framework Convention, which resulted in something called the “Kyoto Protocol” that required the developed industrialized countries — basically the countries of the West and Japan, South Korea — to reduce their emissions, but it was never ratified in the United States, in part, because it didn’t include the countries where emissions were growing rapidly like China, India, and others. So the effort to get the whole world going in the same direction was really at a fulcrum in the run-up to the negotiations that took place in Copenhagen.

President Barack Obama: What we realized was, we’re going to have to create a new framework.

John Holdren, former Director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy: The hope was that the countries of the world assembled there would agree on specific commitments to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. But the model at Copenhagen was, unfortunately, not up to the task. And there was too much divergence.

The Copenhagen meeting was nearly a complete fiasco, except that President Obama himself was able to at least partially rescue it.

Carol Browner: The president had run for office on the issue. He had started to deliver on the issue. And so when we got to Copenhagen, we were a significant player.

The tension there was between the developing countries and the developed. You had Brazil, India, China, sort of banding together to say, the developed world needs to do more. The president had bilateral meetings with each of the delegations — meaning the head of state for India or China, or their lead negotiator….one of our advance guys came back and said, the Chinese are upstairs, they’re meeting with the Brazilians and the Indians. President Obama said, “Let’s go.”

What was great about that moment is he sat there with them and it was not a staged, staff-driven conversation. It was a legitimate conversation between world leaders on what they could do. Some parts of it were quite tense. There was a very complicated exchange with the Chinese. But in the end, President Obama had a piece of paper and was writing out sort of what the outlines of an agreement would be.

We left there and we went over to meet with the Europeans — there weren’t enough seats, so some world leaders were on the floor. Angela Merkel was the chancellor and quite significant in that conversation. It was tough, but you could see the president was focused on, how do you make this happen? What do we need to do?

Of all the government settings I’ve been in throughout my career, this may have been the most intense. If the US doesn’t go to Copenhagen with the president demonstrating action, you’re not going to get what you [later] got in Paris.

John Holdren: In the end, all that could be agreed there was the idea that the world as a whole should be aiming to limit the increase in global average surface temperature to two degrees Celsius above the pre-industrial level. Agreeing to a target implies that your country is going to be on board in taking specific steps to do your country’s part in reaching that target. And that’s why it was at least a step forward that everybody agreed to it. But it fell far short of agreement on the specifics of what countries would undertake.

President Barack Obama: What we were able to do through a lot of negotiations and diplomacy, was to get China, India, Brazil, some of the countries that previously had had no responsibilities to accept that, yes, we’ve got to do something, even as the United States and European countries and Japan and other wealthy nations did something as well.

That initial agreement gave us at least the basis for then negotiating a broader agreement. What that meant was for the next several years in every meeting I had with every foreign leader, climate change was an agenda item.

Executive Action and Legislative Obstacles

Throughout 2009 and 2010, the Obama administration worked to pass legislation through Congress that would address climate change.

Lisa Jackson: The president was really clear that the best way to address climate change was with legislation from Congress that was made specifically for greenhouse gases. Instead, all the rules that we were making [through executive action] were for more conventional forms of pollution, of which one could be greenhouse gases.

Carol Browner: We did begin early on a conversation with Congress. Democrats were in power and very interested in addressing climate change. It was an economy wide approach — what do you do across the economy to address climate change? And that proved to be very, very difficult.

Steven Chu: In the first year, President Obama came into office, swept the House, swept the Senate….then all of a sudden opposition started to form. Energy is a very regional thing in the United States, and it becomes very regional in politics. And in order to get some federal legislation done, you really have to bring people along.

Carol Browner: There are Democratic members [of the House of Representatives]….who would say they probably lost because they voted with us [on the climate bill]. There was never a vote in the Senate.

At the end of the day, even between the Democrats (Opens in a new tab), you had those who were more aligned with our bold view of action and some who were more narrowly focused on specific sectors. And we were never able to bridge that gap. And you had health care (Opens in a new tab). So you had another major, major change in the economy moving along and time being eaten up.

In some ways the clock ran out. It wasn’t for lack of trying.

John Holdren: It was clear that we were not going to get the Congress aligned behind major measures to address climate, so we had to use executive authority.

John Podesta: In the second term, he had the Recovery Act to build on, the big clean energy investments to build on. But still, there was so much more to do, and it was such a crisis facing the globe on everything from the extreme weather that we feel today, to the effects on human security across the globe, including in the United States. One of the roots of the immigration challenge is people losing their livelihoods in Central America and trying to just escape to a place that’s a more livable environment. It’s multi-dimensional. He understood that, and he wanted to tackle it.

Ben Rhodes: The Obama years were a time when you started to feel a budding bottom up activism. My experience of this would have been that in 2009 at Copenhagen, when that did not accomplish what people wanted, there was a very organized environmentalist and activist community that was disappointed, but it had not reached the state of a kind of mass movement that could really hold leaders’ feet to the fire.

I felt like that was changing by 2012. I remember being out on the campaign trail with President Obama and seeing the young people that made up such a key element that the Obama coalition and their number one issue increasingly was climate change. Suddenly you had a sense that this was a voting issue for people, particularly young people. And then you saw organizing, taking place in different communities. You saw certain cities coming to the forefront in terms of climate activism. You started to see that kind of groundswell of a bottom up insistence that this be taken seriously as an issue. And that both creates useful pressure on the administration, but it also creates a dynamic where when President Obama was taking action, that is going to invite opposition.

John Podesta: In the summer of 2013, President Obama gave a very important speech at Georgetown University and laid out a Climate Action Plan that he was setting up for his whole government to basically participate in trying to tackle the climate crisis… he knew that he had a lot of authority, as President of United States, to move his government in this direction. He wanted to leave office having made this really a fundamental part of what he wanted to get done for the American people.

Watch President Obama lay out the pillars of his Climate Action Plan that was announced in 2013.

Weekly Address: Confronting the Growing Threat of Climate Change

A Breakthrough With China and the Path to Paris

The President’s Climate Action Plan (Opens in a new tab) laid out plans for executive action on climate change in his second term. It included a host of measures to make America’s cities, towns, and communities more resilient to severe extreme weather events that come with climate change, and dozens of federal actions to reduce America’s carbon emissions. These commitments were bolstered with public appearances, such as a three day trip to Alaska (Opens in a new tab), to highlight the ongoing effects of the climate crisis and the need to take action — ultimately leading to a nine percent reduction (Opens in a new tab) in America’s carbon pollution by the time President Obama left office.

In parallel to that domestic work, President Obama continued to raise climate change directly with other world leaders in hopes of creating the global agreement with concrete commitments that had proved elusive in Copenhagen. A breakthrough in China ultimately paved the way for success in Paris at COP21 in December 2015.

President Barack Obama: I think a lot of foreign leaders were accustomed to presidents talking to them about the world economy, about terrorism, and issues of war and peace. And what my team and I said is that, “We’re going to make sure that not a meeting goes by where we’re also not mentioning the importance of climate change to the wellbeing of all of our people.”

That was particularly important with respect to China, because China was viewed as the leader of the developing countries, and was really setting the tone for objecting to having any responsibility to do something about their carbon emissions.

John Podesta: There was no higher priority than getting this right with China, because, again, if China didn’t get on track to begin to stabilize, peak its emissions, and begin to bring them down, then the rest of the world really couldn’t be successful.

President Barack Obama: We figured if we could get China on board, then you now had the two largest emitters — the United States and China, a traditionally wealthy country and a country that is still developing — if we got both those countries on board, then we could bring on others. So in my first meeting with President Xi in 2013 (Opens in a new tab), I proposed to him, “Let’s make this a top priority for U.S.-China cooperation.” And he agreed.

John Podesta: The one concrete action that President Obama and President Xi took at that very early meeting in 2013 was an agreement to work together to try to achieve a global treaty, a global agreement to reduce a very highly polluting greenhouse gas thousands of times more powerful than CO2 called hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), used in cooling and refrigeration.

As a result of diplomacy from the president, from the White House, from Secretary of State John Kerry and others, that treaty, which is less known, was signed in Kigali and known as the Kigali Agreement (Opens in a new tab), which is an amendment to the treaty that preserved the ozone layer, the Montreal Protocol. So very early in the relationship with President Xi, even as the friction in the US-China relationship kept getting more severe, the climate track was a place where the two leaders could find cooperation.

President Barack Obama: For the next couple of years, there were a bunch of negotiations back and forth, but eventually, we agreed that we would both come up with targets, that we would pledge to meet those targets and allow for monitoring of whether or not we were meeting our targets for reducing emissions.

John Holdren: “Our two countries are the world’s two biggest economies. We’re the two biggest emitters of greenhouse gases. We together, recognize that this problem of global climate disruption from the accumulation of these gases in the atmosphere is a surpassing challenge for the 21st century, and we are prepared to lead in the world’s efforts to address it.” That statement by President Xi and President Obama Obama in Beijing in November 2014, transformed the international discussion of climate change and climate change policy.

Travels with the President: On Board in China

John Podesta: The effect of that can’t be overstated (Opens in a new tab), because it really galvanized the talks. It made people realize that both the United States and China were both serious about trying to tackle the greenhouse gas problem in their own economies, and it spurred others to action. It really gave a lift to the overall global negotiations.

President Barack Obama: It still wasn’t easy though, because you had countries like India, for example, that made understandable arguments: “We’re not fully electrified yet, we’ve got people in poverty who don’t emit any carbon, and so we can’t sacrifice our development and try to pull people out of poverty and give them electricity and give them transportation just so that you guys in wealthy countries can keep on driving SUVs and run your air conditioners.” That’s not fair. So we had to sit there and negotiate.

John Podesta: President Obama made climate a key part of his bilateral diplomacy with other countries. He was trying to nudge them to greater action, to push them towards getting onboard. One of the factors is that you have to have unanimity in order to move these negotiations forward and anybody can be a spoiler in that kind of a system. So it took tremendous focus and personal diplomacy, a one-on-one, look them in the eye, “What are you going to do?” and really having a strategy about what the United States could do to help countries achieve those goals.

President Barack Obama: There would be an acknowledgement that poor countries wouldn’t have to do the exact same thing that wealthy countries do, that there would be a differentiated response. That wealthier countries would have an obligation to do more, to bring down their carbon emissions than poor countries. That we would help provide technologies that poor countries could still produce electricity, for example, but not emit as much carbon dioxide. But what wasn’t acceptable was countries just sitting on the sidelines, because even if the United States and Europe and the other wealthy countries did everything they needed to do to bring down their carbon emissions, at the pace China and India and other countries were going, we’d still end up overheating the planet and see the oceans rise and create chaos.

John Podesta: He made it a personal part of his diplomacy, to share his perspective on the threat the world faced, the need for a common commitment, the fact that humankind itself was on the line here if political leaders didn’t step up and act.

That personal diplomacy was really critical, because when you’re at the end and there’s hang-ups and you can’t quite get there, it’s the ability of the president to pick up the phone, to call the leader of the other country, to say, “Your negotiators are the sticking point right now. You’ve got to give them instruction to find an honorable path forward.” The president was able to do that in countries in the Middle East, in India, in China. There was a spirit of cooperation, that led to the sort of solidarity we saw at Paris.

Watch former Deputy National Security Advisor Ben Rhodes explain the non-governmental actions that were part of the Paris Accord.

The One Planet We've Got: Ben Rhodes

Ben Rhodes: One of the things that is not well appreciated about Paris and what became the evolving global infrastructure for dealing with climate change is the degree to which activity outside of government policy can play a significant role.

In a lot of other countries, there were movements that were environmental in nature, but they didn’t always connect to climate. So sometimes you had movements against deforestation in Southeast Asia. Sometimes you had movements for much greater air quality — even in places like China — that was certainly the case in India as well. And so what began to evolve is people drawing a connection between local environmental issues, like bad air quality, forests being cut down, and connecting that to this global necessity of taking on the climate crisis. And that was very much a dynamic that grew into Paris.

President Barack Obama: Ultimately, we were able to lineup every country just about to get on board by the time we arrived in Paris.

Ben Rhodes: The key elements of Paris were stacking together a sufficient number of national commitments so that you’re limiting global warming to at least no more than two degrees Celsius. And the goal ultimately is you’re limiting it to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

Every nation involved in the Paris agreement had to make their own national commitment for reducing their emissions over a five-year period. And at the same time, you want to make sure that there’s accountability behind those commitments. So there was a process of reporting on your progress and transparency.

Another really important part of this is that some of the richer countries can obviously make commitments and spend money to do things, to transform their economies, but the developing countries could rightly say, look, we’re being asked to develop without the dirty forms of energy that rich countries used.

So Paris set up an infrastructure where richer countries could help pay for and subsidize the development of clean energy in poorer countries to avoid the kind of emissions that accompanied the development, say, of the United States.

The Work That Remains

President Barack Obama: We all knew at the time that Paris by itself doesn’t solve the climate crisis, because what it did was ask every country to set its own goals for reducing its greenhouse gases. And we knew that some countries were not going to be as ambitious as they needed to be, that the transition from a dirty energy economy to a clean energy economy was going to be disruptive and wouldn’t happen overnight. But our basic assumption was once we got everybody signed on, once we had the architecture for a global agreement, then with each successive year, we could try to negotiate for greater and greater reductions. More and more ambitious goals.

John Podesta: Paris is absolutely worth celebrating because it created the framework of global solidarity and action. We need countries to do more, but Paris provides the framework for demanding more.

President Barack Obama: A testimony to, I think, its resilience was the fact that my successor in the White House decided unilaterally to pull out of the Paris Accords. And yet, despite what could have been a huge symbolic blow that collapsed the entire agreement, every other country in the world stuck with it. So although we were on the sidelines, all the other major countries said, no, we’re going to keep on going. And now we’ve got a US government that once again is prepared to take leadership in this process.

Meanwhile, you have cities and corporations and the private sector and the nonprofit sector all working to continue moving the boulder up the hill. I am optimistic that on this fifth anniversary with all the evidence that we’re seeing of how severe climate changes can be in disrupting our day-to-day lives…that people are going to say we need to speed up. We’ve got to move faster.

Colette Pichon Battle, Obama Foundation Fellow & Founder, Gulf Coast Center for Law and Poverty (Opens in a new tab): There’s nothing we can do as one nation to stop this thing. We’re going to have to move as a global community if we have any hope of getting through this.

President Barack Obama: The thing that I continue to want to insist on is that we’ve got no time to lose. Paris gives us the vehicle through which to bring about the changes that are necessary, but what’s still required is the will and the activism of citizens pushing their governments to be ambitious and to meet this challenge.

Juan Carlos Monterrey-Gómez (Opens in a new tab), Obama Foundation Scholar & Panama Climate Negotiator: I do think Paris is worth celebrating. However, as anything that you love in the world, there is always room for improvement. It was the best outcome that we could get at that precise moment in history. It is also important to remember that they are three main goals of the agreement. Number one, limiting the temperature rise. Goal number two, to build resilience and allow populations and ecosystems to adapt to the impacts of the climate crisis. Thirdly, which I actually believe is probably the most important one, is to align the global financial systems with the objective of limiting the temperature and building resilience. Because at the end, money talks, and if we do not align financial flows to Paris goals, then there is no way that we’re going to be able to keep [the goal of limiting the global temperature rise to] 1.5 [degrees Celsius] alive.

Luisa Neubauer, Obama Foundation Europe Leader & Friday for Future Climate Activist: We organize climate strikes pretty much in every corner of the world, asking our leaders to stick to the promises they’ve made with the Paris agreement.

The way we are working is made possible through that agreement because we have something to point at. We have a promise that’s been made that we now can take and ask to be fulfilled. That’s crucial, very crucial. But those promises, like the Paris agreement, have a very bitter sweet taste because we know they’re necessary, but we haven’t seen world leaders actually sticking to those promises.

John Podesta: Even as the ink was dry on the Paris Agreement, people understood that the collection of commitments that countries had made would not be enough. The UN just recently released a report that basically said, if everybody did all they’ve pledged to do so far, we’d see global average temperatures rise by about 2.7 degrees Celsius.

That is beyond catastrophic. And the science has continued to get better and more clear that we need to stay as close to 1.5 degrees Celsius as is humanly possible. The difference between 1.5 and 2.7, it doesn’t sound like much, but what they were able to predict with a high degree of certainty is the difference between the collapse of virtually every coral reef in the world, the loss of Marine life, the devastation from rising sea level, the devastation from drought, heat waves, loss of food systems, the water systems. And I think that shook the world up.

Colette Pichon Battle: I live in the oil and gas state of Louisiana, so we don’t often see or feel the impacts of say a march in New York or even a protest in Paris. That’s not where we will see the connection in a place like the Gulf South. What we do see, however, are more allies, more folks standing with us. Folks who work in oil and gas, folks who depend on that industry are now armed with the information they need to take their own stand against the local laws, permits, changes that are happening or, and even more drilling sometimes.

This is the change that we’ve been able to see at the ground level. It’s not always what people want to talk about, but as an organizer, power on the ground is what you want to see. And it starts low, it starts as a hum, but then it will leapfrog and propel up in a way that you’ll never imagine.

John Holdren: We need everybody. We need governments. We need businesses. We need universities. And we need mayors, governors, and city planners. At every level, there is much that can be done and needs to be done.

The biggest impacts are impacts that need to be funded and facilitated by government, and by business. We need a major increase in investments, in research, development and demonstration of low emission energy technologies. We need a big increase in investments in advanced approaches to adaptation to the changes in climate that we can no longer avoid.

Watch former Secretary of Energy Steven Chu describe advancements in technology necessary for the climate fight.

The One Planet We've Got: Steven Chu

John Holdren: We need citizens to insist to their policymakers that the policies be constructed and implemented in a way that addresses this challenge, which is ultimately going to affect everybody.

John Podesta: I understand people’s frustration, particularly young people, because there’s a generational equity issue involved in climate change. They’re going to experience the negative effects of bad decisions that their parents, grandparents, and great grandparents made. But I also understand the opportunity, which is right in front of us, to change our economy, to make it more just, more equitable, to reduce emissions, to make it cleaner, and the opportunity to build a strong economy that again, is carbon neutral. That is investing in these new clean technologies like electric vehicles, clean power, reducing emissions from the industrial sector, will create the jobs, the livelihoods, the businesses of the future.

Colette Pichon Battle: I’m not doing any of this alone. And I think what I’m most hopeful about are the hundreds of leaders we’ve been able to connect with now… seeing new leaders, seeing wisdom from so many years all come together like a good gumbo is what gives me a lot of energy and a lot of pride in doing this work. We’re nowhere near done. We have some more, very difficult challenges, obstacles and fights in front of us. But I do think we’re reaching a moment where the broader public is starting to understand that those of us who’ve been talking about climate for decades now have been telling the truth.

John Podesta: The politics of climate have changed. I think the American public has always supported clean energy solutions, and that’s true across the political spectrum. When you ask people, “Do you support renewable energy? Do you support the movement towards electric vehicles? Do you support more money for transit?” You get majorities saying, “Yes, yes we do.” But it hadn’t been a salient issue. It hadn’t been one in which people judged “Do I vote for this person or that person based on their stance on climate?”

I think that’s really changed. As people who have felt the effects of climate change, see it all around them, breathe the smoke from the fires, see the tragedy of people dying from heat, understand the intensity and the increase in flooding in hurricanes, it’s really fundamentally changed, and people are demanding answers.

We need action in this decade. And so, this upcoming meeting in Glasgow is really critical to ensure that the whole world is pushing forward now with even a tougher goal of meeting that mid-century net-zero target.

President Barack Obama: From the perspective of the Obama Foundation, one of the things I’m most excited about is to see the young activists from around the world who are taking up the baton and not just working in their own countries, but now forming a collective movement across borders to tell the older generation that has gotten us into this mess that we all have an obligation to dig our way out of it. And if old folks won’t do it, get out of the way because these young folks are coming and they’re ready to make sure that we have a sustainable planet and a better future for our kids and our grandkids.

- Programs

- Girls Opportunity Alliance

- Health & Wellbeing

- Education

- Building the Center

- Youth